If there was one lesson COVID-19 taught us, it’s that inequality is pervasive

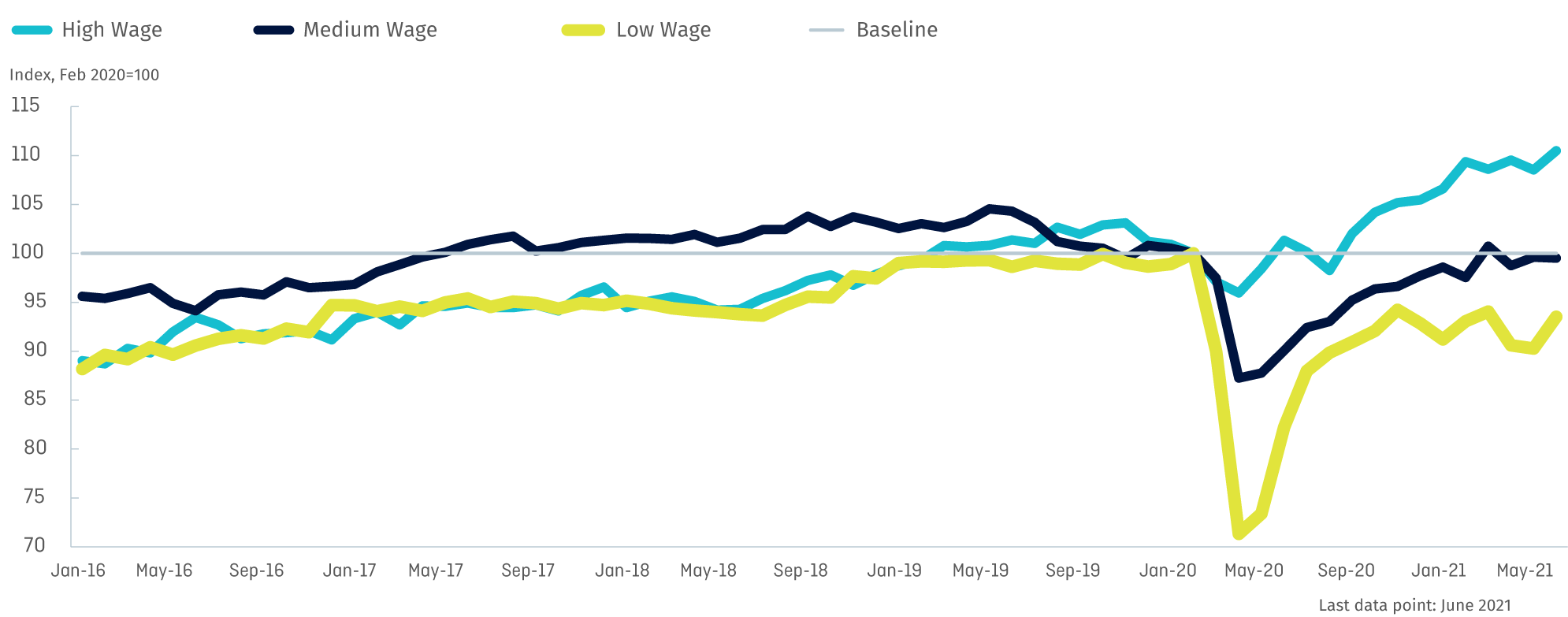

As evidenced by the pandemic, lower-income and socially marginalized populations have fewer resources to protect themselves when natural disasters occur – and workers who are part of these demographics are the first to face job losses and other economic setbacks (see Figure 1). Climate change is no different.

Figure 1: Employment Levels by Wage Tier, British Columbia

Source: BC Real Estate Association; Stats Canada, July 2021

In response to the pandemic, many policymakers have called for global cities to ensure a green and just recovery – one that overturns long-standing social and economic inequalities. As C40 argues, “the recovery should not be a return to ‘business as usual’ because that is a world on track for 3 degrees Celsius more of overheating.”

With this in mind, what’s the next step for cities as we champion a just transition? Or perhaps we can take a step back: what is the just transition, and why should you care?

Figure 2: C40 Mayors’ Agenda for a Green and Just Recovery

- The recovery should not be a return to “business as usual” — because that is a world on track for 3°C more of over-heating.

- The recovery, above all, must be guided by an adherence to public health and scientific expertise, in order to assure the safety of those who live in our cities.

- Excellent public services, public investment and increased community resilience will form the most effective basis for the recovery.

- The recovery must address issues of equity that have been laid bare by the impact of the crisis — for example, workers who are now recognized as essential should be celebrated and compensated accordingly and policies must support people living in informal settlements.

- The recovery must improve the resilience of our cities and communities. Therefore, investments should be made to protect the against future threats — including the climate crisis — and to support those people impacted by climate and health risks.

- Climate action can help accelerate economic recovery and enhance social equity, through the use of new technologies and the creation of new industries and new jobs. These will drive wider benefits four our residents, workers, students, businesses and visitors.

- We commit to doing everything in our power and the power of our city governments to ensure that the recovery from COVID-19 is healthy, equitable and sustainable.

- We commit to using our collective voices and individual actions to ensure that national governments support both cities and the investments needed in cities, to deliver an economic recovery that is healthy, equitable and sustainable.

- We commit to using our collective voices and individual actions to ensure that international and regional institutions invest directly in cities to support a healthy, equitable and sustainable recovery.

Source: C40, 2021

The concept of a “just transition” has been used more frequently since it was adopted by the Paris Agreement in 2015. During the 2021 Canadian federal election, we saw the English-language leaders’ debate focus on climate change, economic diversification and a responsible transition. International bodies – such as the International Labour Organization, C40, and the OECD – have all published numerous research and reports related to the just transition. But while the just transition is seeing a resurgence, the idea isn’t new. It’s been around for decades.

Birth of an idea

The term “just transition” originated in the 1970s, when Tony Mazzocchi, a trade unionist working in the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers’ Union, sought the aid of environmental groups in his fight against the Shell company over safety and health issues. Collectively, they advocated for action to address workers’ livelihoods and preservation of the natural environment. Since then, the use of a just transition has evolved to suit environmental justice and/or labour needs.

What is a just transition?

Throughout the years, multiple definitions of “just transition” have emerged. However, after researching and compiling several literature reviews, Vancouver Economic Commission (VEC) believes the most accurate definition combines the work of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA), the Stanley Foundation, and the C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group. For the purposes of this project, VEC defines a just transition for Vancouver as:

While there is no universal approach to a just transition, there are two broad types of planning this work has engaged with: environmental justice and climate action.

- Environmental justice is drawn out of American anti-racist work, where communities of colour advocated to remove institutions or facilities that negatively affect residents through pollution, waste, and other environmental impacts. Environmental justice framing around the just transition stresses the need for transformative social change that addresses long-standing social inequalities.

- A climate action approach to the just transition more narrowly focuses on workers facing job losses or other negative economic impacts associated with climate change. While generally rooted in a moral call to protect the rights of workers and communities, just transition work may prioritize climate-related impacts and policy considerations, rather than a larger agenda of transformation.

Andrea Reimer, Founder and Principal of Tawâw Strategies, former three-term Vancouver councilor (2008-2018)

How can Vancouver become a global leader in a just transition?

Past efforts at transition planning have been identified in the CCPA BC’s research as governments “throwing money at the problem” with little planning or foresight. Going forward, local governments need to be prepared to play a leading role in just transition work. “Cities are on the frontlines,” acknowledges C40 Cities, a leading coalition of mayors of big cites – including Vancouver – taking urgent action on climate change. “Cities are both where the problems are most serious and where the solutions are being found.”

In 2020, the City of Vancouver approved the Climate Emergency Action Plan (CEAP), positioning Vancouver to reach a 50 percent reduction of carbon pollution by 2030. Specifically, CEAP calls for the creation of a “Zero Emissions Economic Transition Action Plan” (ZEETAP), which aims to “identify and pursue economic benefits generated [by CEAP]” and “provide a just transition for workers impacted by climate action transition” to ensure a healthy economy and clean environment can coexist.

Most of the just transition work in Canada and around the world has focused on coal-reliant economies and rural communities. However, Vancouver’s economic landscape is distinctive – we have one of the most decarbonized economies in Canada. By achieving a successful just transition, we are poised to become a just transition leader not only in Canada, but globally as well.

What does a just transition mean for workers in Vancouver?

The buildings and vehicles sectors are two of the largest contributors to greenhouse gas emissions in Vancouver and Metro Vancouver – and they face a large and fragmented sector of employment. Because of this, a just transition in these sectors must consider independent workers not represented by unions or other organizations.

“Energy transition will create many new industries but it will also lead to contraction of other industries,” explains Sandeep Pai, the Centre for Strategic and International Studies’ senior research lead. “But when an industry declines, there are seen and unseen impacts on local communities. These impacts can range from job losses, revenue losses to loss of social spending. Therefore, any just transition would require planning for all categories of impacted stakeholders.”

Challenges to a just transition for these sectors could be magnified as they navigate through skills and labour shortages. As there is a boost in retiring workers, there is a decrease in younger and diverse workers (especially women and people of colour) who feel comfortable entering these trades and industries. Plus, many independent workers who are not represented by unions or other organizations may be overlooked when it comes to providing workforce transition support.

“A just transition to a green economy [in Vancouver] requires us to think about all workers,” says Irene Lanzinger, former president of the BC Federation of Labour. “Workers are on a spectrum of job quality – some workers have great jobs and will keep them; some workers will lose good jobs in dirty industries, and they will need options and support. We will need to provide opportunities for workers who have been marginalized and excluded in the current job market. Most workers that will need help are in low-wage jobs with no benefits and limited prospects. As we plan our future, we need to ensure that everyone has access to education, training and a good job – one with family-supporting wages and benefits in a sustainable economic system.”

Next steps to realize a just transition in Vancouver

Since the discussion of a just transition has only recently gained local traction, there remains a great deal of work to do. With so few successful case studies outside of coal or fossil-fuel reliant communities, there are many gaps in research and understanding that VEC and others can address moving forward, including:

- Approaches to integrating environmental justice and a “transition to justice” in labour market planning in Vancouver, to better serve communities that have, and continue to face, various forms of marginalization.

- Understanding how the impacts of just transition planning and approaches in Metro Vancouver will be felt in the rest of British Columbia.

- Understanding how to engage the finance sector in just transition planning, particularly larger institutional investors.

- Identifying ways to leverage and align with existing work done locally or provincially that may not be listed under, but is still relevant to, just transition work, such as the CleanBC Job Readiness Plan, the Industry Training Authority’s Skilled Trades Certification Program, and Vancouver Regional Construction Association (VRCA) Construction Workforce of Tomorrow project.

- Working with school boards in the region, and post-secondary institutions, to review and audit programs and courses of significance for decarbonization; and to conduct future labour market projections of the green economy and integrate these in clear, accessible communications to workers.

Best Practices for a Just Transition in Vancouver

This report features a high-level definition of what a just transition could mean for Vancouver. Read it for a jurisdictional overview of just transition practices, analysis of global case studies, context for impending labour transitions in two of the city’s highest-emitting sectors (transportation and buildings), and governance recommendations for the next steps forward in our region.